by Jennifer Zhan, opinions editor

Consol’s biotech class is hoping their research will go viral.

The students used zebrafish to test whether intramuscular vaccines, given as shots, or mucosal vaccines, given as nasal sprays, elicit a higher immune response.

“Since zebrafish are jawed vertebrates, they are model organisms of the human immune system. If we find out what does really good things in zebrafish, we can directly apply [our findings] to humans in studies,” senior Sydney Pham said.

The experiment was divided into four groups: a control, a sterile saline injection control, an intramuscular experimental and a mucosal experimental.

“The logistics of the experiment were very confusing at the beginning,” senior Erica Branham said. “Mr. Young gave us the idea, but we had to be the people that executed it. I would meet with two other people at a Starbucks and spend a couple hours just discussing how we were going to do this.”

One of the biggest challenges was figuring out how to efficiently analyze the fish’s blood samples.

“Last year they were using blood smears, which is when you literally just squeeze blood out onto a slide and count each cell,” senior Christi Koufteros said. “We don’t have time to do that because this year we had 200 fish, not 10 fish.”

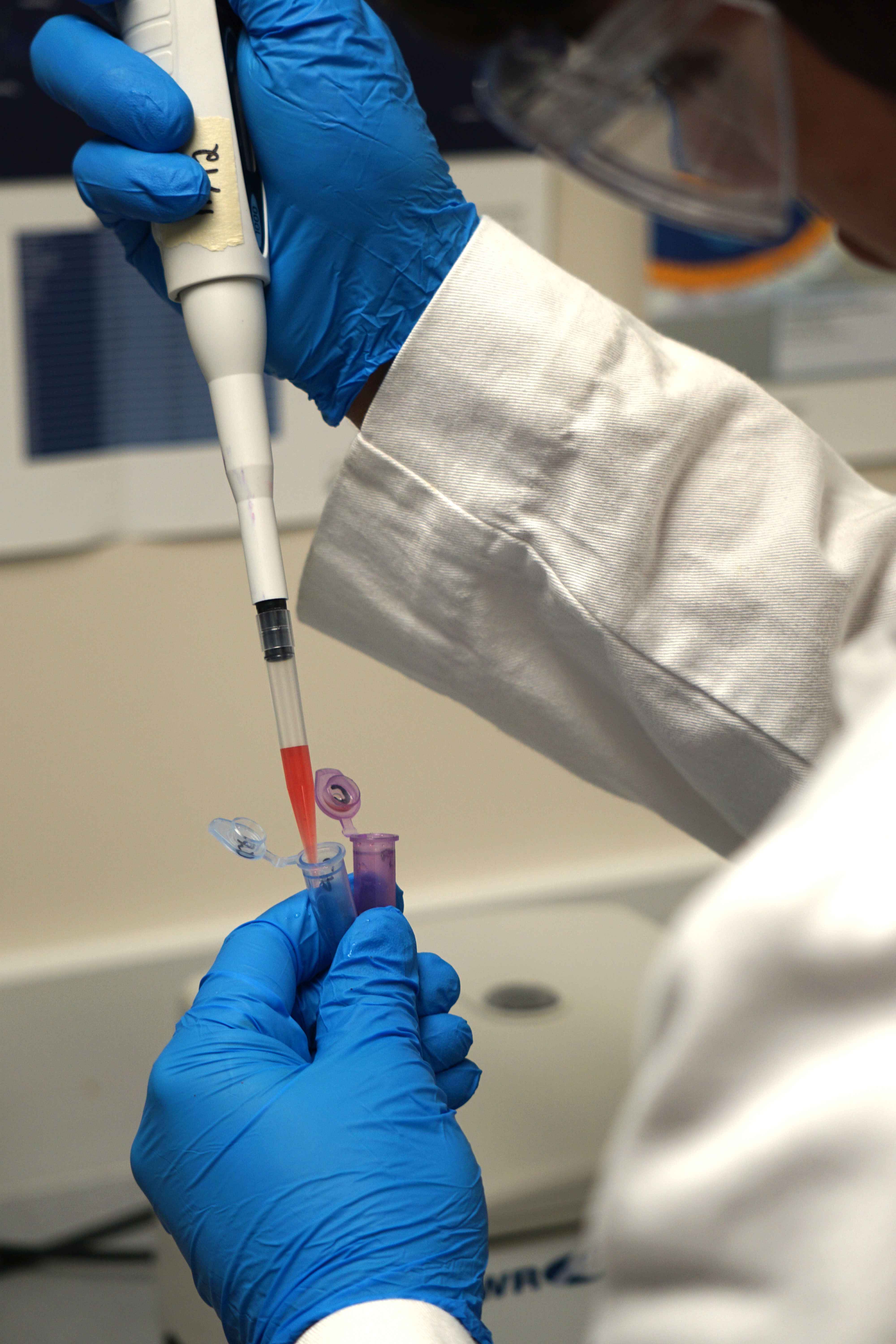

Koufteros was in charge of removing blood directly from the fish’s hearts and preparing it for flow cytometry, a process where a machine shoots lasers at blood and the resulting refraction is analyzed to show what types of cells are present.

“We faced a lot of struggles,” Koufteros said. “We had to email professors trying to talk them into letting us use their half a million dollar [flow cytometry] machine, and then had to figure out how to get blood out of the fish, only to realize that the blood clots immediately, figuring out how to unclot the blood, and then figuring out that you actually can’t just use unclotted blood, you have to use lysed blood, and then figuring out lysis…it wasn’t easy.”

The time-sensitive windows involved in this process meant that the students had to allow for days of preparation before each experiment cycle. This often meant extra work for students involved in this process.

“We’ll euthanize some fish, draw their blood, and process the blood. That has to take place within a ten second window, before it clots, and then all of that data has to be analyzed at A&M within three hours,” biotech teacher Matt Young said. “So we don’t really have time to go, ‘Oops, we don’t have enough glassware,’ or have to clean it.”

The project didn’t only demand the time of students involved in flow cytometry.

“In my group, we took the gills and the guts of the fish after treatment to them to the A&M

lab to do qPCR. You isolate the RNA from the dissection, do cDNA on it, make complementary DNA for the RNA strands, and then run it through a PCR machine,” Pham said. “That actually takes a long time. Over the past two weeks we spent over 60 hours in the lab working on that, on top of work in class and sometimes before and after school.”

The qPCR data showed a greater specific immune response in the fish who were treated mucosally rather than viscerally. In mid-May, 11 students from the class traveled to Seattle to present the project’s full findings in front of the major immunologists of the world.

“The American Association of Immunology Conference in Seattle is not a high school science fair; it’s a national and international conference with keynote speakers of Health Organization projects, for example, the people that are trying to control the outbreak of Zika virus,” Young said. “So they actually [went] and [got] real experience in a professional level arena.”

Branham said that the response to their presentation was overwhelmingly positive, although they encountered one critic who disliked the setup of their experiment.

“The people in that group were able to justify and explain things nicely. Biotech has given us so much confidence to just go out there and talk about what we know, because we do know very much from this class,” Branham said.

Several of the students were mistaken for medical students or PhD students due to their knowledge and skill.

“The fact that we’re able to be comparable to these type of people means that this class is just on a completely different level from a regular science class. But we’re still severely underfunded,” Branham said. “Whenever we were trying to get money to go to Seattle, it was a disaster. The school district didn’t want to give us money, even though this is an incredible thing that we’re doing. We fought really hard on that.”

Over the course of this project, the students had to learn how to work together.

“When we started our immunology project, it was a totally different dynamic. We had to work together as an entire class and that was kind of awkward getting used to,” Branham said. “At first we didn’t really mesh well, but towards the end we were like a well-oiled machine. We knew exactly what we needed to do and when we needed to do it.”

Young says what his students have accomplished this year demonstrates what direction education should be heading.

“We need to be pushing students more, not lowering standards. You can go ask any of my students, none of them had a particular interest in immunology before they started,” Young said. “But look at what these 18 year old men and women are doing. I’ve done almost nothing this year. I gave them some tools, I gave them an objective, and I gave them the opportunity to do it. They did things that are publishable and recognizable and hard to do. You just need to give students the opportunity to do something, and they’ll do it, across the board.”