by Annie Zhang & Stephanie Palazzolo, editor-in-chief & managing editor

Senior Chloe Jackson* was only ten years old when her 15-year-old cousin told her that he wanted to “play a game.”

A few minutes later, she became one of the almost 18 million American women who are victims of rape.

“He was my idol,” Jackson said. “I was just like, ‘Well, he probably knows better than me. He’s smarter than me, he’s older, of course he knows what’s better for me.’ I was very impressionable at the time, [and] you just don’t even think about it being wrong when it’s someone that close to you.”

Although she didn’t realize that she had been raped until freshman year, Jackson started seeing a psychiatrist for depression in the sixth grade. Despite the therapy, she found her life falling apart as she entered high school, and only then started to understand exactly what had happened to her.

DEPRESSION & COUNSELING

“I had physical stress [freshman year] because I was waking up really early, mental stress because of homework everyday and emotional stress… I just reached that threshold of ‘I can’t do this anymore,’” Jackson said. “I lost it. I went into this really bad spiral of depression and anxiety. I eventually took a bottle of pills to school one day and told a teacher I was going to take them if I didn’t get help.”

After the incident, Jackson couldn’t find comfort in her parents, who were called by the school authorities, or in the psychiatric hospital she was admitted to.

“My mom just comes in and is like, ‘What do you want? I don’t know what you want!’ I said, ‘Take me to a hospital,’” Jackson said. “They couldn’t find a psychiatric hospital to send me to that had a bed open, so I waited for 16 hours in the emergency room. Finally they had one, but the hospital was really bad — it was an inner-city hospital [with] constant fights.”

Four days later, Jackson came back to school, where everything seemed to be fine again until January.

“All of a sudden, it just hit again, and I couldn’t keep it together,” Jackson said. “I swallowed a bottle of mouthwash, which had alcohol in it, and took a bunch of pills I could find at home, [but they weren’t] the type of pills that kill you; [they] just made me vomit.”

Nonetheless, her parents sent her to the psychiatrist again, who recommended a better hospital this time.

“[The hospital] kind of helped, but at the same time, it didn’t,” Jackson said. “You see kids in worse situation than yourself, so you start feeling bad about yourself.”

When she returned to school a few weeks later, Jackson fell behind in her schoolwork, which added to her stress and anxiety.

“They put me on a lot of medication, so I just kind of dissociated from myself,” Jackson said. “One day in history class, I took some scissors and just went at my arm for some reason — that’s, like, not something that [I] do regularly; that wasn’t me. But it happened, and of course they had to send me back. That last time, I just had enough.”

Jackson finally revealed to her parents that she had been sexually assaulted by her cousin. She recalled that she “couldn’t even be in the room when [her psychiatrist] told [her] parents.”

However, she was now faced with a more difficult question: to press charges or not?

“[My assailant] was, like, the cousin who was supposed to take over the family farm, and my grandpa wrote a paper in a farmer’s magazine about how great he was,” Jackson said. “So everyone was going to side with my cousin, not [with] me about it. Who’s going to believe the youngest one rather than the well-respected one?”

In the end, Jackson decided to not pursue charges.

“It’s that threshold of, ‘Am I going to screw everything — everything else — up in my life?’” Jackson said. “It wouldn’t help [my cousin’s] family because they’re poor, and he’s the breadwinner for his family. I know that if I would have pursued action, [my family] would have dissipated completely.”

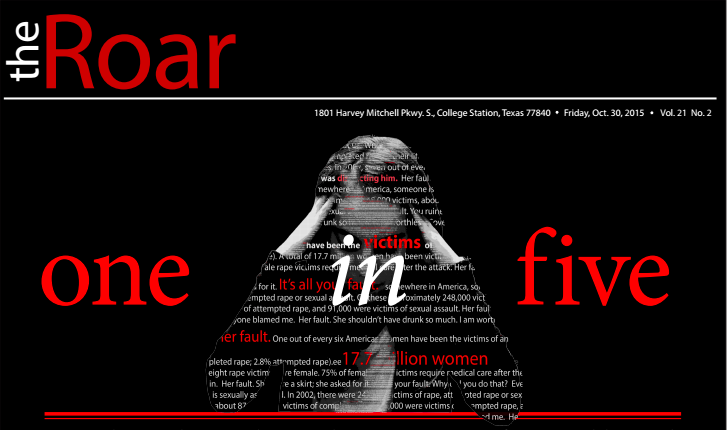

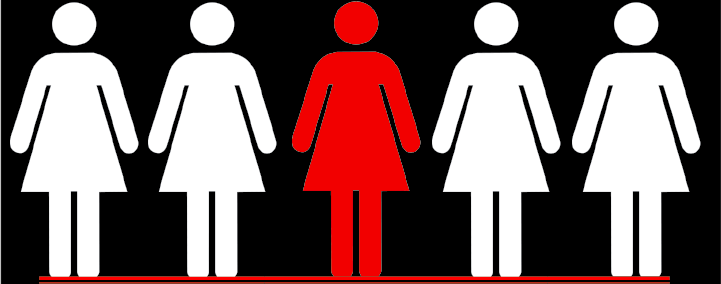

Jackson’s decision isn’t uncommon — 63% of all rape cases are never reported to the authorities — and her story is just one of millions. According to a poll conducted by the National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence, one out of five women is a victim of rape or attempted rape.

“The numbers fluctuate, [depending] on whether the victims report or not,” Jasmine Rodriguez, the Victim’s Advocate from the College Station Police Department, said. “One year, we could have victims report, report, report, and then the next year, it can be like, ‘No one’s reporting, what’s going on?’”

Last year, College Station had 34 reported cases of sexual assault and 15 cases of child sexual assaults. But for many survivors of sexual assault — both those who choose to report and those who don’t — rape often becomes the root of other problems, such as depression, anxiety and low self-esteem.

“[I felt] worthless,” Jackson said. “I didn’t like the way I looked; I was uncomfortable with my body, just uncomfortable with everything about myself. I didn’t like who I acted as, I didn’t like anything about myself. I’m still not really comfortable with my body, and I guess if you analyze it, you could connect the dots that way.”

Doctors prescribed her medication for her depression, and at one point, Jackson was visiting therapists three times a week.

“I’m still on medication to this day; I take eight or nine pills a night. It’s just a long process,” Jackson said. “I wouldn’t say I’m in ‘remission,’ but once you’re diagnosed with major depression or generalized anxiety disorder, it’s not like it’s something you can get rid of. You’ll always have it, [but] it’s just [that] sometimes it’s worse than other times.”

At the end of freshman year, Jackson found herself ranked far below her expectations in her grade, as she struggled to balance her schoolwork and mental health.

“Imagine where I could have been if that wouldn’t have happened, if I wouldn’t have missed almost a month and a half of school?” Jackson said. “That’s the part that kind of haunts me — I could have been something so much better than what I am now, not directly because of [the sexual assault], but because I missed school because of it.”

Still, Consol and its counselors seek to serve as a primary advocate for victims and to act as an intermediary between student and teachers.

“We make sure that school doesn’t interfere with what they’re experiencing or going through,” counselor Paul Hord said. “School takes the last priority because their priority is their care. We try to find them resources outside of school — the biggest one right now is SARC.”

The Sexual Assault Resource Center, or SARC, is a local non-profit organization that provides free and confidential counseling for sexual assault victims and anyone else affected.

With a 24/7 hotline and on-call advocates that provide comfort for victims during the legal and criminal justice process, SARC also offers free educational programs and training to academic, civic, professional, and community organizations.

“There is no time frame for healing from a sexually violent act; therefore, we see clients ages 13 and up who may have been assaulted as a child, in a marriage or a dating relationship — any point in time,” SARC’s program director Tracey Calanog said.

Even when legal action doesn’t pan out, SARC and the counseling it offers can help victims return to some semblance of a normal life.

“That’s the best way to go, that healing path, because if you think about it, you have the criminal justice system and you have your mental health path,” Rodriguez said. “If [a person’s] case is dismissed or doesn’t go through, they can still have that healing path, and that’s what counts, their mental health.”

And for Jackson, help in the form of counseling and therapy allowed her to recover from her mental trauma.

“I probably wouldn’t be where I am today if I wouldn’t have told anybody. If your situation is giving enough that you can actually get help, go get help,” Jackson said. “You can’t live with it forever; something’s going to explode at some point. [You] need to be able to get it out before [it] gets to that point.”

VICTIM-SHAMING

Another obstacles victims of sexual assault face in getting the help they need is overcoming the societal stigma surrounding sexual assault.

“When I went into that downward spiral, my dad was the one who was, like, ‘Why would you do this to the family?’” Jackson said. “Even after I told them, there’s still always that sense that in some way, it’s the victim’s fault. It’s a popular culture thing, like, ‘Oh, she was wearing something distracting,’ but when you’re ten years old, that doesn’t really line up correctly with that logic. But still that logic is used. Somehow it’s my fault.”

And it is exactly this fear of societally-imposed guilt that illustrates why less than 40% of all rape cases are ever reported.

“Women are afraid to report, because they’re afraid to be told that they ruined the man’s life, when in reality, the man ruined her life,” senior Jane Reed*, a friend whom Jackson turned to for additional support, said. “It sticks with you like nothing else: a rapist can be released from prison, but a girl that is raped can never have that experience not happen to her. Trauma does not go away after time. It stays with you.”

This perspective of guilt was further declared when earlier this year, Rolling Stone published a controversial article about a college student who claimed she was raped at a fraternity. The report was later proved by authorities and other media sources to have been fabricated by the source.

“I think it’s disgusting that people would do that. I don’t know what this girl’s end game was, but to think that she would make up something so traumatic that actually affects one in five women — a very upsetting statistic — is very gross,” Reed said. “There’s really no excuse for doing something like that when it’s not true, and you have no idea what the trauma another person’s going through feels like.”

Despite that prevalent ideology, Rodriguez has emphasized that the violation of the survivor’s body “isn’t their fault,” and SARC has pledged to “help in any way [they] can.”

“Sexual assault and violence, in general, is never okay. If you, or someone you love, has been hurt by a violent act, we will be there to support and listen to you,” Calanog said. “You never have to go through anything alone.”

Jackson found most of this additional support through her friends, including Reed and senior Fred Smith*.

“I was more angry than anything on her behalf, because she is someone I care about and I know she had her trust and bodily autonomy violated in such a horrible way,” Smith said. “People weren’t listening to her; her family, to this day, hasn’t done anything about it. It’s a really sad situation.”

PROBLEMS & SOLUTIONS

That such a close friend had been raped revealed the pervasiveness of the “rape culture” to both Smith and Reed.

“After I found out that she’d been actually raped, [the issue of rape] was more serious; it wasn’t as abstract. Like, she’s the one in five women who’s a part of this,” Reed said. “It’s a real thing that’s actually happening; it’s a real thing to be afraid of. It needs to be addressed, that girls at such a young age — twelve or thirteen — are getting abused like this.”

The problem, Jackson suggests, “lies with [our] abstinence-only education.”

“It works back to the victim being at fault instead of people taking responsibility for their actions. Even on Facebook, it’ll be a picture of a girl scantily dressed and people comment, ‘Oh, well, she’s asking for it,’” Jackson said. “We don’t teach consent, we just teach, ‘Never have sex.’ The rates of pregnancies and STDs are higher that way, and there’s just a general lack of education about what’s okay with sex and what’s not okay.”

Rodriguez agrees that the key to changes in our societal beliefs is awareness and education.

“It’s easy to blame the victim, to [say that] well, she shouldn’t have drunk so much. If the victim cannot make that choice because she’s wasted or something like that, [then] that other person should have the moral value to say, ‘Well, she’s passed out; I’m not going to do that,’” Rodriguez said. “It’s individual choice, it’s self-control.”

Consol too has considered covering the topic of consent, but so far, nothing has been finalized.

“It’s hard to do at a school setting because it’s so taboo. There are some things students need to be aware of [with] the law, but beyond that, the biggest one is consent,” Hord said. “It’s actually something that we’ve discussed as a school, but then we’re trying to figure out how and when to do that. The topic needs to be, somehow, covered with the 1800 students.”

Another aspect of the problem is the abundance of “rape jokes,” especially within the high school demography.

“We need to stop trivializing sexual assault and start actually teaching people that it’s a really bad thing to do, and that it sticks with people forever,” Reed said. “The most important thing that we can do is speak out against it — if you hear somebody saying something like that, be like, ‘That’s not funny. If you think that rape is funny, you’re a horrible person.’ Just make sure people know that rape is not something you should talk about lightly, because it’s not a light subject.”

Though Jackson acknowledges that “we can’t change a culture overnight,” she believes that “the microaggressions that provide this background for rape” can be eliminated.

“It’s all sorts of little things. If you’re teaching a boy that it’s [a girl’s] fault that he’s distracted, then you’re teaching him that it’s okay to take advantage of her because she’s dressed with parts of her body showing,” Jackson said. “I could understand if someone showed up to school in a thong and a bra, like, that’s distracting. But [society’s] willing to take her out of school for a whole day because it might distract a boy.”

SEVEN YEARS LATER

Jackson attributes her ability to so clearly and calmly reflect on what happened to her seven years ago to the help and support she received from her friends, teachers, psychiatrist and her own self.

“A lot of people, when they’re going through puberty and growing up, they get a sense of self. And since I had to overcome so much more in that same period that everybody else was going through, I feel like I came out on top,” Jackson said. “I know who I am, I know what I like to do, I know what I want to do in my life, and I know I can do it. I feel really strongly about who I am now.”

Certainly, Jackson’s past will continue to live within her, but with several leadership positions and a strong GPA, Jackson has indeed found herself again.

“If you’re just looking at me from the outside, you wouldn’t know what’s happened to me,” Jackson said. “I’m not trying to be cocky, but I’m where I am right now, [and] I feel good knowing that I’ve gotten to this point.”

Today, Jackson has become an advocate for sexual assault victims, particularly for the LGBTQ, who are often targeted because of their sexual orientation.

“Being an ally in that way and making myself available to talk about those things helps the situation for other people,” Jackson said. “I’m not scared of people knowing. If it can help someone out, if it can help even save a life, if [it can] prevent one really bad instance, then it’s worth it.”

*Name has been changed to protect the identity of the source.

This story first appeared in Volume 21, Issue 2 of the print edition of The Roar.